William Knabe: Founding of a Legacy

|

Beginnings

The son of a pharmacist, William Knabe (1803-1864) was born on June 3, 1803 in the little German town of Kreuzberg (now Creuzberg). [1] With Johann Sebastian Bach having been born over a century before in Eisenach, not far from Knabe’s birthplace, the region of Knabe’s birth was rich with music history. But unlike Bach, the original family plan for young Knabe was not musical—his father had originally planned to train him in the family profession of apothecary (similar to modern pharmacy). But Napoleon’s invasion of Germany devastated the Knabe family’s fortunes and put to rest any thought of paying for the required University training. Young William Knabe looked for other options and came across the idea of training to be a cabinet maker. It was a far cry from his intended field, but William Knabe became good at it, and he used his developing skills to step into a new purpose in the world of music: piano building. |

A few years into his cabinetry training, Knabe found an apprenticeship with the piano maker Langenhahn in the town of Goth, Germany. As he learned the trade, he soon became recognized in many of the principal towns of Germany as an excellent piano maker. Knabe’s reputation, coupled with the continued rise of the piano’s importance in nineteenth-century Germany, should have resulted in a stable and successful career in the German piano industry. But, as often happens in life and fiction, William Knabe fell in love, and that changed everything. The year was 1831—Knabe was now 28 years old—and the young lady’s name was Christina Ritz.

To America With Love

Dr. Ernest Ritz, the well-to-do patriarch of the Ritz family, accepted William Knabe into the fold and agreed to the impending marriage. However, the family was on the brink of a decision to immigrate to the New World. Christina’s brother had established himself as a farmer in Hermann, Missouri, and the family was anxious to hear whether life in the New World was worth the voyage. Considering that a Russian cholera epidemic had arrived in Germany in 1831, the Ritz family must have been overjoyed when they received good reports from Missouri. The matter was settled—the family would be moving from Germany to Missouri, and William Knabe was invited to join them. The wedding could wait until they arrived in America.

Dr. Ernest Ritz, the well-to-do patriarch of the Ritz family, accepted William Knabe into the fold and agreed to the impending marriage. However, the family was on the brink of a decision to immigrate to the New World. Christina’s brother had established himself as a farmer in Hermann, Missouri, and the family was anxious to hear whether life in the New World was worth the voyage. Considering that a Russian cholera epidemic had arrived in Germany in 1831, the Ritz family must have been overjoyed when they received good reports from Missouri. The matter was settled—the family would be moving from Germany to Missouri, and William Knabe was invited to join them. The wedding could wait until they arrived in America.

|

Love-struck young William Knabe the piano maker undertook the voyage across the Atlantic with the intention of becoming become William Knabe the farmer, but the difficulty of the voyage ended up changing his plans. Tragedy struck when Knabe’s father in law-to-be, Dr. Ritz, became seriously ill and died during the voyage. The absence of the patriarch who led the Ritz family migration must have been a serious blow to their morale. When they arrived at the port of Baltimore in 1833, William Knabe and the Ritz family could not bring themselves to continue the difficult journey to Missouri, and a decision was made to remain in Baltimore, at least for a year. Perhaps it would be best, they thought, to acclimate to the language and culture of America first before moving west.

|

A New Life in Baltimore

William Knabe and Christina Ritz married in Baltimore that year, and the new couple set about seeking to establish themselves financially as they settled into the American way of life. Knabe must have been excited to discover that Baltimore was home to a growing piano-building industry. Rather than seeking to earn a living in the newly intended field of agriculture, Knabe took an American apprenticeship in the field he was best at, and he began working for piano builder Henry Hartge for five dollars per week (Hartge was also an immigrant from Germany and

|

inventor of the piano’s iron-plated pin block). Hartge recognized Knabe’s skill and dedication and soon raised him to eight dollars per week. As fate would have it, Knabe’s success as a piano builder overshadowed his family’s intended move to farm life in Missouri. Knabe ended up remaining with Hartge for four years, during which time he saved up a significant amount of money. Rather than moving on to Missouri, he decided to use his savings to establish his own business in Baltimore. Knabe sold his remaining farm equipment and purchased an old frame building on the corner of Lexington and Liberty Streets out of which he could service and rebuild pianos. The year was 1837, and the Knabe Piano Company was born.

|

Building a Legacy

|

After its humble beginnings, the Knabe piano business took a bold step in 1839 with the decision to begin building new instruments. Additional equipment and capital was needed, and for that, William Knabe formed a partnership with piano builder Henry Gaehle. The firm was renamed “Knabe and Gaehle,” and their pianos soon earned wide respect. Perhaps the most famous instrument built by the firm from this time is an elaborate square piano commissioned by Francis Scott Key (author of America’s National Anthem) and built in 1840. Francis Scott Key enjoyed the piano for a few years before his death in 1843—it may now be seen on display in The Peabody Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee.

|

As the business grew, the company had to move to larger locations more than once. In 1841, the company moved to the corner of Liberty and German Streets (where the Baltimore arena is now located), then to Eutaw and Cowpen Alley in 1843 (current location of the Hippodrome Theater), after which the company rented warehouses in 1847 on North Eutaw, and finally the adding of facilities on Baltimore Street near Paca in 1851. The Knabe and Gaehle Company’s success was undeniable, but fires at its facilities in 1854 challenged its continued growth.

On November 5, 1854, the Knabe and Gaehle facility on Eutaw street was destroyed in a fire that collapsed the walls of their building and nearly cost the lives of the firemen fighting the blaze. And on December 9 of the same year, the Knabe and Gaehle facilities on Baltimore Street went up in smoke. The company’s insurance coverage was minimal and the loss was great. The stress may have contributed to Gaehle’s death in 1855, but William Knabe was determined to recover. He bought out Gaehle’s share of the company and continued on as William Knabe & Company, and he relocated to new facilities at an old paper mill on West and China streets. In a push to move forward, he competed for and was awarded a gold medal by the Maryland Institute during that same year (for having the best piano exhibited at its fair).

|

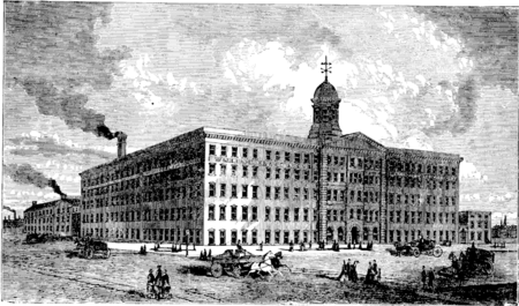

More awards would follow, which helped contribute to a continued need for expansion, and in 1861 he commenced construction of the final Knabe Piano Factory building at the corner of Eutaw and West streets (where the M&T Bank Stadium is now located). The completed factory, a large building that was a commanding presence in South Baltimore, was finished in 1869 with a cupola (now on display at the Baltimore Museum of Industry) that could be seen for miles in every direction. “One of the largest and best” (Mayer, 351) piano factories in the United States, the Knabe building became a Baltimore landmark which could not be missed by travelers entering the city by train through the nearby Baltimore and Ohio Railroad depot.

|

Through Fire and War

For William Knabe, the fires of 1854 were a tremendous challenge, but perhaps the greatest challenge of his career began in 1861, the year after he started construction of his newest facility. On April 12 of that year, the first shots of the Civil War were fired, and within a short period, almost all of Knabe’s customer base (mainly in the South) dried up. The company did what it could to survive, but it may have been too much for William Knabe. He passed away on May 21st, 1864, nearly a year before the Civil War ended, and control of the company passed to his sons. Knabe’s death did not go unnoticed. One obituary called him a “well-known and much esteemed citizen” (Chronicles of Baltimore, pg. 629). Brantz Mayer, author of Baltimore: Past and Present, commented about William Knabe’s character:

For William Knabe, the fires of 1854 were a tremendous challenge, but perhaps the greatest challenge of his career began in 1861, the year after he started construction of his newest facility. On April 12 of that year, the first shots of the Civil War were fired, and within a short period, almost all of Knabe’s customer base (mainly in the South) dried up. The company did what it could to survive, but it may have been too much for William Knabe. He passed away on May 21st, 1864, nearly a year before the Civil War ended, and control of the company passed to his sons. Knabe’s death did not go unnoticed. One obituary called him a “well-known and much esteemed citizen” (Chronicles of Baltimore, pg. 629). Brantz Mayer, author of Baltimore: Past and Present, commented about William Knabe’s character:

|

[Knabe pursued his occupation] with unflinching energy and resolution. He bore his reverses with equanimity, continued faithful to his engagements under all circumstances, and in the face of disaster and impending ruin, maintained a cheerfulness and decision of character, worthy of imitation as well as praise” (pg. 498).

A man made great by his character and contributions, William Knabe was sorely missed. But his legacy lived on. |

Next Generations: Transforming America

William Knabe's Sons

After their father’s death in 1864, William Knabe’s sons Ernest (1837-94) and William II (1841-89) (and later his son-in-law Charles Keidel) assumed control of William Knabe & Company. Having received a first-class education, and having been trained by their father in the intricacies of piano building, the Knabe sons were well-equipped to oversee every aspect of the business. William, the more reserved of the two, took the role of managing the factories, while Ernest became the official head and representative of the company. With the Civil War having ravaged their clientele in the South, Ernest’s first order of business was to discover new markets and keep the Knabe Company from failing. He decided to travel through the northern and western states in order to establish new agencies for the sale of Knabe pianos.

In preparation for his trip, Ernest visited the Knabe Company’s bank to request $20,000 in operating funds. The end of the Civil War was a difficult time for most, and such a request would certainly have strained the Baltimore city bank. When asked about collateral available for the loan, Ernest could offer “nothing but the name of Knabe,” and his request was declined. When asked what he’d be able to do without the loan, Ernest told the bank officer, "I shall go down to my factory and tell my employees that I am compelled to discharge them all because your bank refused a loan to which I am entitled." (Dolge, 329)

Considering the importance the Knabe Company to Baltimore, such a scenario would have been a major blow to the city. Ernest picked up his hat and left the bank to return to the factory. As he entered the building and started to his office, a messenger from the bank arrived with a letter from the bank’s president. Ernest, surprised, opened and read that the Knabe Company had been approved for the requested loan.

Ernest proceeded with his 1864 trip, and it was a great success. In two short months, he had made the connections he needed to place William Knabe and Company firmly back on its feet, including establishment of an agency in New York City. As the firm grew and flourished, he later opened offices in Washington, D.C. and built additional factory space. William Knabe and Company grew from a regional name to a national one. With requests for pianos made in the next few decades from European buyers and from the government of Japan, Ernest’s tenure saw the Knabe name reaching through three continents.

Considering the importance the Knabe Company to Baltimore, such a scenario would have been a major blow to the city. Ernest picked up his hat and left the bank to return to the factory. As he entered the building and started to his office, a messenger from the bank arrived with a letter from the bank’s president. Ernest, surprised, opened and read that the Knabe Company had been approved for the requested loan.

Ernest proceeded with his 1864 trip, and it was a great success. In two short months, he had made the connections he needed to place William Knabe and Company firmly back on its feet, including establishment of an agency in New York City. As the firm grew and flourished, he later opened offices in Washington, D.C. and built additional factory space. William Knabe and Company grew from a regional name to a national one. With requests for pianos made in the next few decades from European buyers and from the government of Japan, Ernest’s tenure saw the Knabe name reaching through three continents.

William Knabe's Grandsons

It was quite tragic for the Knabe family when William Knabe II died in 1889 at the young age of 47. Ernest Knabe followed in 1894 and his sons, Ernest J. Knabe Jr. (1869-1927) and William Knabe III (1871-1939) became president and vice-president, respectively, of the firm. And in 1908, they led the Knabe Company to join with other brands under the auspices of the American Piano Company, of which Ernest was elected president and William III vice-president. The arrangement, however, did not work out quite the way that Knabe brothers liked, and they withdrew from the firm in 1909. Although the Knabe family was no longer involved, the American Piano Company continued to produce pianos in the William Knabe Piano Company name and tradition. The Knabe name continued to be respected throughout the United States and the world for many years.

It was quite tragic for the Knabe family when William Knabe II died in 1889 at the young age of 47. Ernest Knabe followed in 1894 and his sons, Ernest J. Knabe Jr. (1869-1927) and William Knabe III (1871-1939) became president and vice-president, respectively, of the firm. And in 1908, they led the Knabe Company to join with other brands under the auspices of the American Piano Company, of which Ernest was elected president and William III vice-president. The arrangement, however, did not work out quite the way that Knabe brothers liked, and they withdrew from the firm in 1909. Although the Knabe family was no longer involved, the American Piano Company continued to produce pianos in the William Knabe Piano Company name and tradition. The Knabe name continued to be respected throughout the United States and the world for many years.

Developing Classical Music in America

Undeniably, the Knabe family had a positive economic impact on Maryland and surrounding states, as well as a significant role in the development of the musical instrument industry in American. But it is less known that the Knabe family had a transformative effect on the quality of music in America through their support of great artists. The Knabes’ positive influence on American classical music manifested in many ways, including their sponsorships of von Bülow, Tchaikovsky, Saint-Saëns, Rubinstein, and others.

Undeniably, the Knabe family had a positive economic impact on Maryland and surrounding states, as well as a significant role in the development of the musical instrument industry in American. But it is less known that the Knabe family had a transformative effect on the quality of music in America through their support of great artists. The Knabes’ positive influence on American classical music manifested in many ways, including their sponsorships of von Bülow, Tchaikovsky, Saint-Saëns, Rubinstein, and others.

The German Maestro

Hans von Bülow (1830-94), who was first a student of Clara Schumann’s father (Friederich Wieck) and later of Franz Liszt, came to America in 1889 for a second American concert tour. His first American tour (1876-77) was sponsored in part by Frank Chickering (Chickering Pianos) and was generally considered to be less successful than his second tour.[2] Ernest Knabe sponsored von Bülow’s second tour and provided pianos for his concerts (he performed over a hundred times!) which took place in multiple cities. In Boston (April 1889) von Bülow performed all of Beethoven’s piano sonatas over two days. Just how important was von Bülow was to the American audience? One reviewer put it this way:

Hans von Bülow (1830-94), who was first a student of Clara Schumann’s father (Friederich Wieck) and later of Franz Liszt, came to America in 1889 for a second American concert tour. His first American tour (1876-77) was sponsored in part by Frank Chickering (Chickering Pianos) and was generally considered to be less successful than his second tour.[2] Ernest Knabe sponsored von Bülow’s second tour and provided pianos for his concerts (he performed over a hundred times!) which took place in multiple cities. In Boston (April 1889) von Bülow performed all of Beethoven’s piano sonatas over two days. Just how important was von Bülow was to the American audience? One reviewer put it this way:

|

Tchaikovsky at Carnegie Hall

Perhaps the best-known Knabe-sponsored event took place the following year, during which Ernest Knabe brought Peter Tchaikovsky (1840-93) to America. The primary occasion was the opening of Carnegie Hall on May 5, 1891, for which Tchaikovsky conducted. But Knabe also made arrangements for Tchaikovsky to visit Baltimore and Washington, D.C. Tchaikovsky directed a concert at the old Lyceum Theater on North Charles Street in Baltimore on May 15, 1891, featuring his Serenade for Strings and his first piano concerto (the pianist was the esteemed Adele aus der Ohe). He commented positively about the city and about Ernest Knabe, a “beardless giant” whose “hospitality is on the same colossal scale as his figure.”[4] But despite his positive view of Baltimore, Tchaikovsky was relieved to share his art in Washington the following day, where he could once again communicate in in his native tongue while at the Russian the embassy. His trio and a quartet by Brahms were performed there. |

|

Tchaikovsky’s final American appearance was in Philadelphia on May 18th, where he conducted the same program that he had in Baltimore. Before boarding the ship for his return him, Ernest Knabe presented Tchaikovsky with a small model of the Statue of Liberty (Tchaikovsky wondered how he’d get the symbol of American freedom past the Tsarist Russian border guards!). When he arrived back to his home near Moscow, a Knabe square piano, courtesy of the Knabe Piano Company, was waiting for him.

|

Knabe's Grandsons as Concert Managers

|

The early twentieth century saw a continued push toward excellence in American Music through the efforts of the Knabe family’s third generation. The Knabe brothers paid considerable expense to sponsor American performances in 1906 by the French composer Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921). Best known today for his composition The Carnival of the Animals, Saint-Saëns became an avid supporter of the Knabe piano, having written in a November, 1906 testimonial:

I simply have the highest opinion of them (Knabe pianos). The ease and evenness of the action, the limpidity and charm of the tone, above all, that rare quality possessed to sustain tone and sing like a human voice, as well as the varieties of the tone color met with, all combine in making the most magnificent and delightful instrument which it is my good fortune to play upon.[5]

|

Also in 1906, the Knabe brothers sponsored the first North American tour of a pianist who was not well-known at the time, but who would later become one of America’s best-loved musicians. The Knabe-sponsored tour included 40 concerts spread over three months, the first of which took place at Carnegie Hall on January 8, 1906. The chosen debut piece was the Saint-Saëns G Minor Piano Concerto, and the soloist at the Knabe concert grand piano was none other than the young Arthur Rubinstein (1887-1982). Although Rubinstein did not become the big Knabe piano supporter that Saint-Saëns became, he developed a warm personal relationship with the Knabe brothers, particularly William Knabe III, and he was fully aware of the contribution that the Knabes made to his career. About his New York debut, Rubinstein wrote:

|

My first concert was a triumph! I was called out for perhaps 12 bows, I have 2 encores, and the audience gave me an ovation. . . . [William] Kabe is delighted, he adores me, I think, as he is so kind to me.[6]

Like Tchaikovsky before him, Rubinstein also performed in Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia. His Baltimore debut took place at the Knabe home, where Rubinstein performed with the celebrated soprano Johanna Gadski (1870-1932) and then enjoyed the famous Knabe hospitality at a large 200-person reception held in his honor. Because the Knabe Company was more deeply involved in concert management during the first decade of the twentieth century, Rubinstein was scheduled to perform in additional cities, including Chicago, Boston, Cincinnati, Providence, and more. |

|

After the Knabe Family

Within two years, the absorption of the Knabe Piano Company by the American Piano Company changed and ultimately reduced the Knabe brothers’ sphere of influence. But the Knabe legacy lived on. In later years, Knabe became the official piano of the Metropolitan Opera; a favorite piano of Presidents Woodrow Wilson, Herbert Hoover, and Lyndon Johnson; and the favorite piano of famous figures like Albert Einstein and Elvis Presley. Today, evidence of Knabe’s important past can be seen at the M&T Stadium (home of the Baltimore Ravens), where a piano mosaic at the Southewest end of the stadium commemorates the Knabe legacy. |

[1] Brantz Mayer (Baltimore: Past and Present) and the British Parliament’s 1877 Reports from Commissioners list William Knabe as having been born in the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar, which would have placed him at modern-day Creuzberg. This location makes sense since he apprenticed in Gotha and later lived in Meiningen, which are all within vicinity of each other. Robert Palmieri (The Piano: An Encyclopedia) gives Knabe’s birthplace as modern-day Kluczbork, Poland (previously Kreuzberg, Germany). This is unlikely since this city was part of the Prussian Empire and not Saxe-Weimar.

[2] Arthur Loesser, 534

[3] The Musical Courier, April 19. Quoted in Alan Walker’s Hans von Bülow: A Life and Times, 409.

[4] The Life and Letters of Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky, 654.

[5] Rollin Smith, 285.

[6] Havey Sachs, 87.

[2] Arthur Loesser, 534

[3] The Musical Courier, April 19. Quoted in Alan Walker’s Hans von Bülow: A Life and Times, 409.

[4] The Life and Letters of Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky, 654.

[5] Rollin Smith, 285.

[6] Havey Sachs, 87.

Contact1-888-978-5332 Ext. 4

[email protected] |

|